Occasionally we take a walk up to Pentire Headland and watch the Cribbar break. The last time we went the whole place was a circus, crowded with big wave surfers, jet-skis, SUPs and guys towing in. The younger crew of semi-pros, rippers and stand out locals were watching, all hoots and “yeews”. There was a smattering of tourists and walkers, wondering what all the fuss was about. After we watched a well-known UK big wave surfer drop down the face of a big lefthander which broke way out on the second reef, my eldest daughter turned to me and said “What was it like when you surfed it Dad?” I could feel the heads of the crew closest to us turn to me, eyes looked my overweight middle-aged frame up and down…someone muttered “bullshit”. I felt the anticipation of those around me, waiting for me to launch into a ‘death or glory’ big wave tall-tale. I thought I heard sniggering. I looked at Daisy and said “It’s scary out there.” The girls watched with me a while longer and then, looking like we’d got lost on the way to Pauline’s Café, we wandered into the Headland Hotel for the cream tea I’d promised them.

I was working for Tim Mellors at Custard Point as the finisher and polisher in the factory on Tolcarne Road, just down from Tall Trees. We had quite a team there: Tim shaped everything by hand, Nick Williams did the artwork, Steve Hendon did the sanding, Nick ‘Noddy’ Carter did the glassing.

Having spent years watching the Cribbar break from the line-up at North Fistral and having hounded all the older guys for information about the wave, through the summer of ‘95 I became determined to paddle out there and surf it. I was 25, I was fit, I’d surfed Fistral as big as it got, throwing myself off the ‘shit-pipe’ jump off rock at the end of South Fistral in huge swells. This was going to be the the year.

The Cribbar, however, had other ideas. The moody old cow refused to break. Sure, I saw some peaks feathering at first peak but the words of wisdom about the Cribbar that Hawaiian Island Creations shaper Alan ‘Mac’ McBride gifted to me, rang in my ears: “That inside first reef shit everyone surfs now? That’s not the Cribbar”. So I waited. Then in the first week of September, I checked the pressure chart and saw a big low out in the Atlantic, slowly lumbering its way up the Gulfstream. It looked just right on the chart….like a big fat onion cut in half, nice tight 960 isobars with favourable winds, high pressure over Cornwall.

I told the crew at Custard Point that Thursday would be the day. If you were thinking that part of my preparation would have involved asking Tim to shape me a big heavy gun for the mission, you would be wrong. A pulled-in diamond tail 9’6” performance longboard with an eye-catching hot rod flame spray had served me well at big Fistral and would have to do.

Early on Thursday morning, I met the guys at the factory. Nick Williams and Nick Carter were up for the challenge. ‘Noddy’ would ride his 9’1” longboard and Nick Williams, in the manner befitting an ex-Lightning Bolt Team Rider, would take a 7’10” semi-gun. We jumped in the cars and drove to Little Fistral.

The tide was low but pushing in, so we wouldn’t have long. On the drive down to the car park, we could see big shifty peaks feathering out on the reef. The sun was blazing and the sky was a cloudless azure blue. The day’s beauty was marred by the sight of line after line of white-water washing across Little Fistral. And it was obvious that the wind was switching round from light offshore to a breezy southerly. I was undeterred. There was no chat or banter. I don’t remember getting changed or waxing up, but I do remember Nick telling us to paddle out near the headland at Little Fistral, as close as possible to the rocks.

The two Nicks timed their entry perfectly and paddled like crazy before the next set rolled through. I faffed around getting my leash on and paddled out about 20 metres behind them. The channel by the rocks was helping but I could see the guys further ahead start to sprint as a bomb set appeared, marching around the headland towards us. I lost sight of them as they went over the first overhead wall. I got halfway up the face and turtle rolled but the lip pulled the board straight out of my hands and in the ensuing mess, I got sucked back by several yards. The next wave was 6 feet of solid white-water. I pushed my board sideways and dived under, only to get dragged back again. When I surfaced and grabbed my board, I was almost back on the beach.

I was furious that having been the instigator of the Cribbar mission, I hadn’t made it out whilst the two Nicks were probably already heading out towards the second reef line-up. Furious with myself, and fuelled by visions of my mates dropping into perfect 15 footers, I sprinted up the beach and over the car-park to the old lifeboat slip-way on the other side of the headland. Ignoring the barnacles and mussels under my feet, I tottered down the rusty steel and concrete slip way, jumped off the end and began paddling the long way around.

It was a long, lonely paddle out across the bay, past Lunvoy rock, past the sewage pipe and through its stinking, brown, scummy foam, and past High Place Rock, with huge swell lines passing underneath me on their way to the town beaches. As I paddled out around Towan Head towards Cribbar Rocks, I could feel the swell size increase and knew I’d need to paddle out wide to avoid getting caught inside.

The first reef peaks looked huge from where I was paddling. I couldn’t see either of the Nicks but tried not to think about what might have happened to them. My arms were aching from the long paddle but as I made it past the first reef line-up I knew I had other problems to deal with. The first was the rip which after every set, was fiercely dragging me away from the line-up and out into the bay, as the Fistral beaches emptied out like toilet bowls. I had to keep paddling to stay in one place. The only other time I’ve experienced a rip that strong was on an Indo trip at Desert Point when the current in the Lombok Straight threatened to drag the whole charter boatload of us back to Bali.

The second problem was obvious to everyone who has ever seen the Cribbar working at size. Contrary to how it looks from South Fistral, it’s a big playing field out there with several different peaks, and impact zones, depending on the angle of the swell. What looks like a perfect right-hander can be met by a left which has broken wide, coming towards you and pinning you in the impact zone. Just lining up out there on that kind of day is almost impossible. I made my way across to where I saw the second reef feathering on the smaller sets, paddling against the rip to stay in position. My plan, if you could call it that, was to pick off a couple of lefts and ride into the relative safety of the deeper water in the channel.

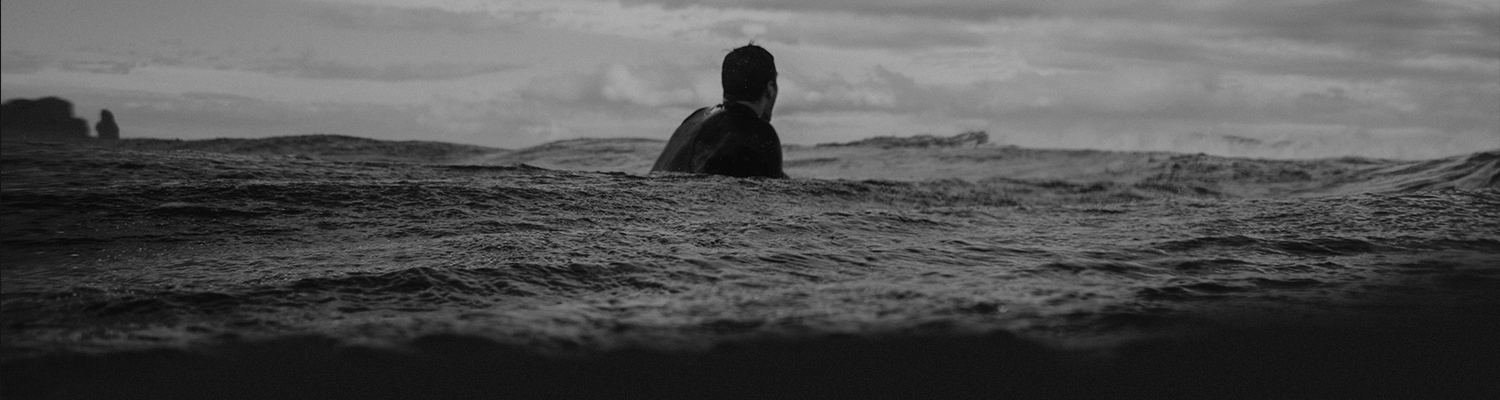

I looked back towards the headland. Fistral looked tiny and miles away. The whole vibe out there was spooky. I scanned the inside and to my dismay, in the distance saw Nick Williams and Nick Carter, paddling away in the channel back towards Little Fistral, their session over. I told myself I wasn’t going back without getting at least one wave. As I turned around, I could see a set feathering and smoking, but not breaking, way outside on the third reef. The wind was picking up and had gone South Westerly, throwing chop onto the surface. paddled against the rip, further into the take-off zone.

As the set approached second reef, it was already starting to feather so I half-heartedly paddled for the first wave, just to get my courage up. The second one was sending smoke back from its lip, and I double arm paddled up the face and over the lip, going airborne as I went over in a shower of spray. The third one was walling up and turning into a big left and I was in a position to give it a decent go.

I turned around and paddled as hard as I could, feeling like I was being chased down by an ocean liner. As the swell came up behind me, I thought I was going too slowly to catch it. Fearful of another wave behind catching me inside, I double arm paddled and felt the board accelerate. I got to my feet and kept low, with my weight forward to keep the board’s wide nose down, as the face fell away below me. The speed was incredible but with the combination of chop on the face and the wave finding its way over the uneven reef, the feeling was like going over a vertical set of moguls. My knees and legs were pistoning up and down and I hung on, desperate not to get thrown off. The face smoothed out at the bottom and I was aware of the silence around me as I leaned into a backhand bottom turn, just as the lip detonated behind me like an artillery gun battery going off. I made a mid-face turn and dropped back down the face again, glancing up at a huge gaping barrel over my shoulder. I kicked out over the shoulder into the safety of the channel.

The adrenaline kicked in and I wanted another so I spent another 15 minutes paddling back around to the peak. By this time, the tide was getting higher and the sets on the second reef were struggling to break. I paddled into another smaller left which broke further in, and which gave me a relatively soft take off and a smoother drop but a shorter ride. As I kicked out, further inside, the jagged rock gullies behind me seemed far too close. I remembered the photos I’d seen of the old timers surfing the Cribbar in the 1960s, and one in particular of a smashed up board which had been pulled out of one of those gullies.

To my growing horror, I saw a big close-out set looming out the back, lining up all the way across where the lefthander breaks. I scratched over the first one but the sectioning lip on the second one was already dropping. I paddled a few more strokes, towards the channel and got off my board, pushing it from the tail, away to the side. I took a deep breath and dived as deep as I could, legs kicking like a Moulan Rouge dancer. As the white-water rolled over me the sound was deafening but just as I thought I’d got away with it, I was grabbed by the scruff of the neck and rag-dolled for what seemed like several minutes. I felt my leash pull taught like a guitar string and then relax, which I took to mean that either the leash, or the board, or more likely both, had snapped.

As the turbulence let me go, I swam up and breathed in a mouthful of foam. I was expecting to be washed straight into the rocks by the wave behind but to my utter relief, the board and my leash were intact and although the rocks were very close, the rip had dragged me out towards the channel. Trying to calm my shredded nerves, I paddled into deep water, sat on my board and counted myself very lucky.

I looked up to see if a crowd had gathered to watch me ride the Cribbar, or drown, but I could only make out an old man walking his dog and paying no attention to me. The tide was now getting high and the fickle Cribbar was turning off again. I began the long paddle back. Although the sun was out, I felt cold and was shivering in my shorty wetsuit which I used to wear from May to October.

About halfway back, a fishing boat chugged past me on the way to the Harbour and one of the fishermen leaned over the side and shouted in a Cornish accent so thick I could barely understand him “You oright boy?! You wanna lift back to the ‘arbourrr?” I politely declined and made it back to the slip way under my own steam.

Back in the car park there was no reception committee, no photographers, no-one to mark the occasion. Even my mates had decided not to hang around and watch. I got changed and warmed up in the car, feeling exhausted and disappointed that it hadn’t been the perfect Cribbar I’d dreamt of surfing for years and that I’d only caught two waves. I drove back to the factory where the two Nicks were waiting, along with Phil Clifford the legendary shaper from Vitamin Sea and Rockit surfboards who was covered in foam dust, having agreed to shape a few shortboards for us.

The two Nicks shrugged and said they’d got a couple but it wasn’t very good over on the rights because of the wind. Phil took his mask off and asked me how many I’d caught. I looked at the floor and told him two lefts. “You went left?” he said. “The left is the proper wave.” I suppressed a smile and told Phil that the southwesterly wind and tide had dampened the experience somewhat. Phil went to put his mask back on and stopped and looked straight at me. “And as far as I know, you’re the first surfer to go left out there since 1967.” There was no holding back the grin that spread across my face as I walked away and the planer screamed into life behind me.

These days, Nick Williams can either be found commentating at the Boardmasters or fibre-glassing flat- roofed buildings. Nick Carter, who Joel Tudor once described as having the most stylish footwork on a longboard he’d ever seen, when he finds the time to get out there, is still the best all-round longboarder in the line-up at Fistral. I’m usually found surfing clean 3-4 footers with my daughter at Perranporth, on a dark blue 10ft heavy traditional longboard, still trying to perfect my drop-knee cutback. When it’s big enough for the Cribbar to break, I’m straight out there….in the line-up at Towan or Great Western.

But I still dream about the Cribbar. Sometimes my teenage daughter, who rides a longboard with real style, asks me if I’d ever surf it again. “Maybe,” I tell her, “if I can lose at least three stone and get in shape.” What I do know is that I have unfinished business out there on that spooky reef. And next time, if there is a next time, I’ve got a 9’6” pintail big wave board sitting in my garage just waiting for that day to come.